(2021 Update)

Future Lari here: If you’re interested in more illustrated food history essays like this, consider checking out my newsletter, RENDERED. It is a continuation of this Food Questions series: free, monthly, in-depth essays, all researched and illustrated by me. Thanks!

Welcome to the second installment of my Food Questions series, where I investigate the stories behind food, just to satisfy my curiosity. (Find installment 1 about Catherine de’Medici here.) Remember: I’m not a historian or food expert, just a hungry, curious blogger asking questions.

People move, taking their customs and ideas with them. Language, culture, music, and food are among the cultural artifacts that that people bring with them in migration.

It’s a story that has repeated itself since the beginning of history.

Italy didn’t have tomatoes until the 16th century, when explorers to the New World brought them from Peru to Europe. Pizza was born in Naples during the 1700’s, and it wasn’t until 1889 that the classic tomato-mozzarella-basil combination wasn’t dubbed the Margherita, after the Queen. Neapolitans took the creation with them to the United States in the early 1900’s, where it exploded in popularity. Thus, in the grand scheme of food history, the ubiquitous pizza is nothing but a baby.

On the other side of the world, tempura (or classic Japanese deep-fried goodness) was originally introduced in the 1500’s by some poor lost Portuguese sailors who found themselves in Japan on the way to Macau. 300 years later, the British found their way to Japan and introduced a dish from one of their imperial colonies: Indian curry. The dish has been reworked to better suit Japanese tastes, and is now one of the country’s supreme foods.

Today’s question is about the influence of cooking traditions and the evolution of those dishes that travel. Specifically, the possible relationship between the Puerto Rican dish, arroz con gandules, and Jollof rice, a West African specialty.

Let’s start with an introduction to arroz con gandules.

Rice (arroz in Spanish) is a staple in Puerto Rican cooking, as it is in many other world cuisines. In her childhood, my grandmother remembers her mother cooking rice dishes as a way to stretch what little meat they had, be it pork, chicken, or seafood. Rice dishes are the bread-and-butter of the Puerto Rican table. Arroz con gandules (“Rice and pigeon peas”) is a dish that is especially important during the end-of-year festivities. As with any classic dish, every home cook has their own spin on the dish, and their own jealously-guarded secret ingredients.

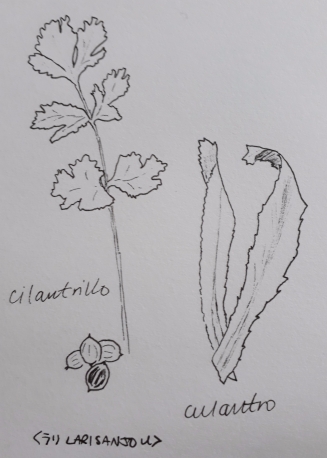

Gandules are pigeon peas, a legume originally from India, which was later brought to Africa, then to the New World. They are small, pert beans that are soft and creamy in the inside. When combined with rice, you have a meal that provides a complete protein.

For my version, I start by rendering the fat from smoked lardons in a heavy-bottomed pot, adding a touch of additional olive oil. Next, homemade sofrito (the base of all Puerto Rican cooking) goes in to bubble with minced garlic, ground coriander, oregano, bay leaf, green olives, tomato purée, and sazón until powerfully fragrant. At this point, I tip in my rinsed gandules, followed by rinsed medium-grain rice, along with enough water to cover by about 2cm. Once the cauldron of lusciousness has simmered to evaporate much of the water, I stir once before tightly covering, lowering the heat, and letting the rice steam itself to completion.

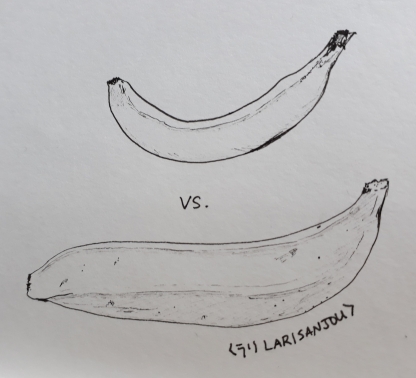

The resulting dish is fluffy grains of fragrant rice that maintain their textural integrity. It can be enjoyed on its own, or served alongside simmered beans, gently fried sweet plantain strips, and fresh avocado. A fantastic comfort food.

I like mine to be a deep red color, from tomato purée and achiote (either from my own infusion of annatto seeds in oil, or in powdered form, as part of any commercial sazón mix).

For another take on this dish, check out chef Meseidy’s version at The Noshery. She features lovely photos, a detailed recipe, and an ingredient breakdown and additional cooking tips.

Today’s food question came to mind when I came upon an article on Jollof rice, a West African rice dish, fluffy long-grain rice seasoned in various manners, over which several countries claim to have perfected, between Nigeria, Cameroon and Ghana, among others. A dish originally made with barley, which was swapped for rice in the 19th century. Traditional ingredients include thyme, scotch bonnet peppers, stock cubes, and curry powder. Drooling over the pictures, I noticed quite a few similarities with my beloved arroz con gandules.

I got to thinking: Could it be that arroz con gandules, the ubiquitous Puerto Rican dish, evolved in tandem with the iconic West African Jollof rice?

Let’s look into the story of Jollof rice. There seems to be some debate as to where the dish originated, but many sources (including this lovely infographic on the food blog Kitchen Butterfly) point to Senegal as the starting point for this dish. The name Jollof comes from Jolof, a ruling center of the empire of the Wolof, in Senegal and the Gambia, from the mid-1300’s to 1890.

During this time, Portuguese trading posts were operating at the Senegal River. This region came to be called the Grain or Rice Coast, for (unsurprisingly) its prolific grain cultivation. Tomatoes came in from the New World, and it is conceivable that the birth of this dish followed thereafter.

Now, to address the slave trade and its role in global movement. This document from the UNESCO archives, written by the late Cuban professor José Luciano Franco, details European slave trade in the Caribbean and Latin America.

Spain and Portugal started importing slaves from West Africa to their soil in the 14th and 15th centuries. After Columbus’s discovery of the New World, as early as 1501, they were quick to move in establishing a transatlantic slave trade, thereby increasing the efficiency with which the New World territories could be exploited. There are records of the Spanish slave trade continuing through the late 1800’s.

At first, African slaves were transported from Spain and Portugal to the New World, but this tactic proved problematic. The Wolof people were specifically mentioned in Professor Franco’s report, as a group who quickly developed a reputation for instigating uprisings and revolts. In an attempt to put the kibosh on those pesky slave uprisings, the Spanish began transporting slaves directly from the African continent to their colonies. The King of Spain even declared that no slaves who had spent more than 2 years in Spain or Portugal were to be transported there. Thus, slave traders ramped up activity in the ports of Guinea, where the trading posts dealt in foodstuffs and human flesh.

Meanwhile, back in Boriken (the original Taíno name for Puerto Rico), the native population didn’t stand a chance. Most of the Taíno were decimated shortly after the arrival of the Spanish–if not by brute human force, then by disease. They themselves left behind no written records. The population of Puerto Rico now consists of the biological remnants of indigenous peoples mixed with European, West African, and Asian ancestry. Starting from the early 16th century, Puerto Rican cuisine was left open to interpretation; ingredients from both the Old and the New Worlds were left to mix with the various cooking methods belonging to the new multiethnic population.

Looking at modern Caribbean cooking, we clearly see other dishes that trace the complex history of transatlantic movement. For example, bacalaítos (delectable seasoned fritters with bacalao, or salt cod) are very similar to Haitian and Trinidadian accra and French-Antillean accras de morue, which seem to share ties with fried bean fritters called akara in West Africa, known as acarajé in Brazil. Indeed, it is a tangled web of food history–perhaps a grand family food tree is needed to give order to it all!

I’m venturing to claim that the connection between jollof rice and arroz con gandules is like that of not-so-distant cousins. They share roots, and evolved in slightly different directions over time. At the heart of it, you’ve got two dishes that start with an intensely flavored tomato-based sauce; add rice that’s been either generously rinsed or parboiled; cook in a tightly-covered vessel, stirring infrequently to ensure the final product is soft and fluffy. Both are also commonly served with fried plantains.

Food is not simply sustenance, but living culture. Our multiracial heritage was born from centuries of European colonization. It has left an indelible mark on our physiognomies, the tongues we speak, the food we eat, and the cultural practices we observe.

Arroz con gandules, a Puerto Rican culinary staple, represents a legacy of our storied past.

Let’s chew on that during this holiday season.

Works Consulted

Carney, Judith A. “Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas: Chapter 1.” Harvard University Press. Accessed 12/21/2017.

Franco, José Luciano. “The Slave Trade in the Caribbean and Latin America from the Fifteenth to the Nineteenth Century.” United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. 28 February 1977. Accessed 12/1/2017.

Sokoh, Ozoz. “An Infographic: A Brief History of Jollof Rice.” KitchenButterfly.com. Published 17 August 2017. Accessed 12/20/2017.

“Part 1: A Short History of Jollof Rice.” Published 19 November 2014. Accessed 12/20/2017.

“Part 2: #Jollofgate – In Defense Of Our Traditions.” Published 20 November 2014. Accessed 12/20/2017.

Sokolov, Raymond. Why We Eat What We Eat. Touchstone, Simon & Schuster, 1991.