(2021 Update)

Future Lari here: If you’re interested in illustrated food history essays like this, consider checking out my newsletter, RENDERED. It is a continuation of this Food Questions series: free, monthly, in-depth essays, all researched and illustrated by me. Thanks!

It’s summer, and many of us associate this season with outdoor gatherings, vacation, the beach, and barbecues. (This year, of course, we have to observe these traditions with the spirit of social distancing.) For me, summer is about the smells: fresh-cut grass, chlorine, and meat on the grill.

While doing some reading, I once came across a tidbit that caught my eye: the word “barbecue” is of Taíno origin.

Taíno origin, you say? I knew I had to investigate.

You, the Reader, may be wondering: Why is it that the word “Taíno” piqued my interest?

I grew up hearing the same thing as many other Puerto Rican kids: “You know, we’re part Taíno!” It was whispered reverently, like a vague promise.

I grew up thinking that the Taíno Amerindians were gone. Our Indigenous ancestors were all either killed by the Spanish, or intermarried with African and European arrivals to the island. It was assumed that any Indigenous blood that was left in our veins was so far removed, it was more of an urban legend.

But this question of identity has been on my mind for as long as I can remember. I always felt like I didn’t fit in. I have fair skin, blue eyes, and light brown hair, so I don’t look “typically” Latin. My native language is English. I was born on the mainland United States. As a child, adults around me would speak in Spanish to have coded conversations, almost like passing on secret messages to each other (surely to protect my little ears from hearing things I shouldn’t). I remember feeling hurt, not because they needed to speak amongst themselves, but that Spanish was used as a tool of exclusion.

I wish I had understood then that to be of Puerto Rican heritage means to be part of a diaspora.

I wanted desperately to fit in, but somehow felt that I would never succeed. I would never be enough. I didn’t look the part, I couldn’t speak Spanish, I wasn’t born there, and my connections to this far-off place were foods brought in via suitcase, music, secondhand stories that I would savor. (I wrote a piece about this experience, called “Suitcase Nuyorican,” which you can read here).

In short, I felt an urgent need to “do my homework.” I started learning Spanish on my own, curled up on the blush-pink carpet of my childhood bedroom, behind my locked door. I’m not sure why I felt the need to be so secretive, but I suspect it’s because I felt I was behind in doing something I should’ve already known how to do. I was behind, and desperately wanted to catch up so that I could prove that I belonged. I didn’t feel like I fit in at school, at gatherings with other Puerto Rican families, or even in my own skin. I felt ashamed of my own existence from A to Z, starting with my cultural identity.

“We’re” part Taíno… but who were “we”? Was I really included in that “we”?

Into my adult life, I wrestled with the idea that I didn’t fit in. So when I first arrived in France, I decided to pursue geneological research and take a DNA test. Once I started researching my family history, and putting myself into the context of my family tree, things started to clear up.

Things further clicked into place for me when I found the death certificate of my great-grandmother’s great-grandfather, born in 1798.

José Maria Cabán y González de ciento seis años, de raza india, de estado viudo, de oficio labrador, natural y vecino de esta jurisdicción, en residencia en el barrio del “poblado” falleció ayer à las diez de la noche à consecuencia de “senectud.”

In the village of Moca, at 4:00 in the afternoon on the twenty-first of September, 1904: […]

José Maria Cabán y González, aged one hundred and six years, of Indian race, widower, farmer by trade, native to this jurisdicion, and residing in the village, died last night at 10:00 as a result of “senescence.”

When I found this document, I remember feeling a jolt. There it was, in black and white.

We really are part Taíno.

And I am part of that “we.”

Thanks to the schoolyard rhyme, we know Christopher Columbus set sail on August 3, 1492, in search of the New World. He landed in the Bahamas, and made contact with the Indigenous people. He described them as such: “They were very well built, with very handsome bodies and very good faces… They do not carry arms or know them… They should be good servants.”

He was describing the people he subsequently dubbed “Taíno.” We don’t know with certainty what they called themselves. “Taíno” is a term that is used today to distinguish Caribbean Arawak peoples of the Greater Antilles from other Arawak tribes of South America and the Lesser Antilles. The Taíno themselves probably had more precise terms to distinguish themselves from community to community, and from island to island. It is understood that Arawak people migrated from modern-day South America, from the Amazon through to Venezuela and the Greater Antilles, spreading from eastern Cuba, to Jamaica, the Bahamas, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Many place names in these Caribbean islands are versions of the original names, and Jamaica’s coat of arms features two Taíno people.

History tells us how the Spaniards (indeed, in the tradition of colonial powers) inflicted brutality upon the Native peoples in the countries they invaded. After a brief period of coexistence, Taíno men were taken to work in gold mines and plantations. This meant there were not enough people to plant crops, leading to widespread starvation, not to mention the devastating effect of New World diseases like smallpox. Some Taínos died while fighting against the Spaniards; others fled; and still others committed suicide to avoid the brunt of Spanish brutality. Many Taíno women married conquistadors, creating a mestizo population. By 1514, 40% of Spanish men had reportedly taken Taíno wives. It has been estimated that 85% of the Taíno population had vanished by the early 1500s. In 1530, the Spanish governor in Puerto Rico sent word back to Spain that there were no Taínos left. We know now that this was an inflated claim, thanks to census counts from the 18th century.

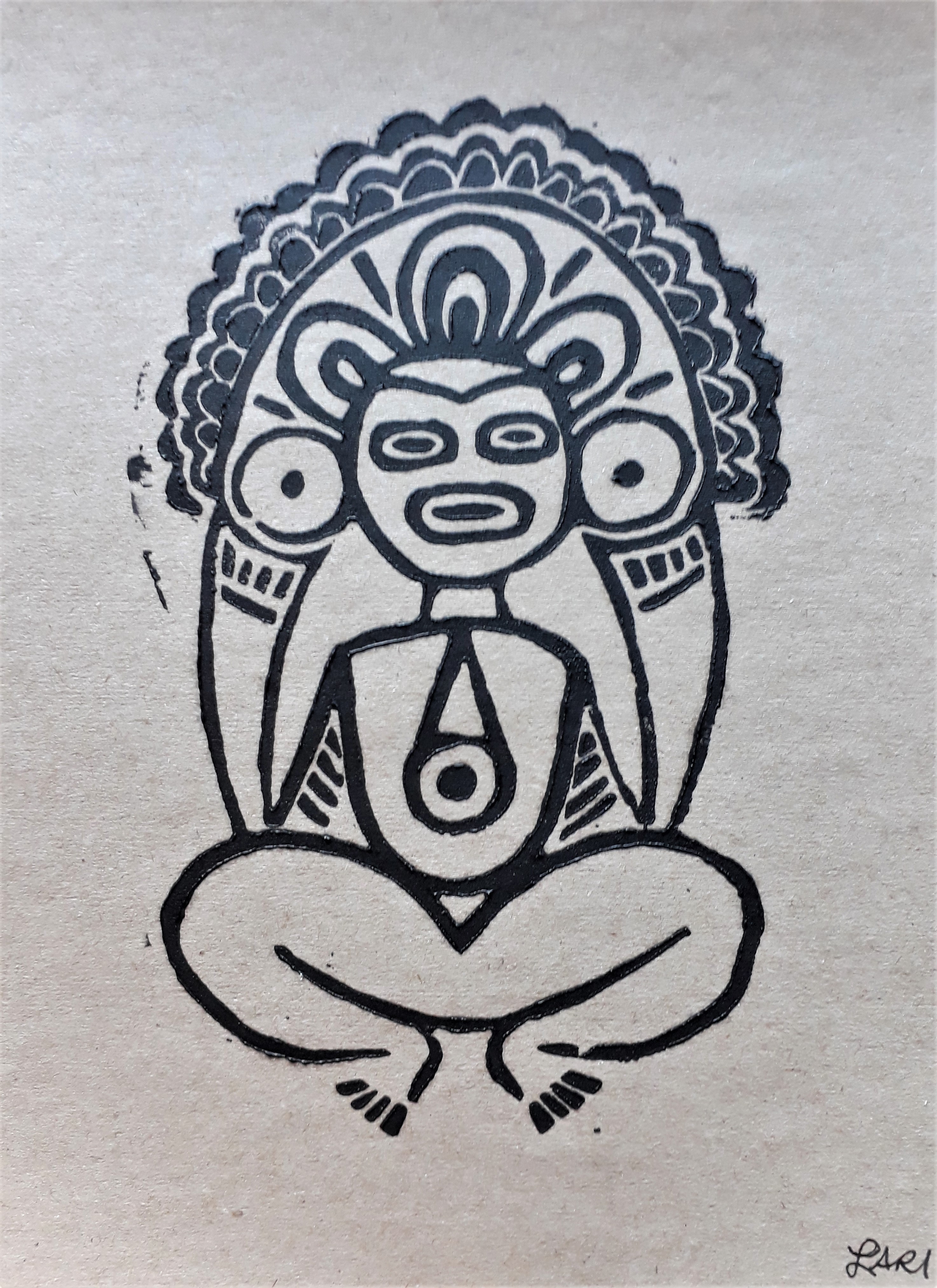

The Taínos did not have a written language, so much of their legacy is based on written accounts by outsiders, the artifacts they left behind, and the vocabulary and customs that have survived to this day. We know they learned how to remove cyanide from yuca (or cassava), and made it into a flatbread called casabe, which is still prepared in Venezuelan, Dominican and Jamaican households (where it is known as a bammy). They lived in dense, well-organized communities; cultivated cotton, dyeing it and weaving it into hammocks and intricate belts; smoked tobacco during religious ceremonies; were well-versed in plants for medicinal use; and were prolific artists. They left behind pottery, petroglyphs, cave paintings, and carved images in wood, shell, stone, and bone. And of course, they gave us vocabulary.

The Spanish word “barbacoa” comes from a similar word in the Taíno Arawak language, which referred to the structure onto which meat or fish was placed, over a fire, for the purpose of roasting or drying. The word was used for the first time in print in Spain in 1526, in a written document by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, in his “Historia natural y general de las Indias.” A “barbecue” consisted of some sticks, arranged like a grill or a trivet, over a hole in the ground, likely used for fish and other animals they hunted. (To learn more, check out this video on Youtube by Eat Drink Share Puerto Rico.)

The earliest known use of the word “barbecue” in the English language dates back to the 17th century, which referred to a wooden framework used for storage or for sleeping upon. In A New Voyage Round the World by William Dampier, published in 1697, it refers to the structure as a place for sleeping: “And lay there all night, upon our Borbecu’s, or frames of Sticks, raised about 3 foot from the Ground.” Interestingly, today in Cuba, this meaning persists. According to Havana City Historian Eusebio Leal Spengler, the term is used to refer to constructions that citizens of Old Havana make to divide a room, creating more habitable space. A barbacoa, or a bench made from reeds, may also be used to sleep on. The existence of this word is explained by the influx of people into Havana from all regions of the country, including eastern Cuba, where it is known to be an ancestral Taíno territory. It is therefore assumed that eastern Cubans brought this lexicon with them.

In the 18th century, “barbecue” in English took on the meaning of “food cooked over a fire.” In 1755, “barbecue” first appeared in Samuel Johnson’s The Dictionary of the English Language, defined as follows: “to ba’rbecue. A term used in the West-Indies for dressing a hog whole; which, being split to the backbone, is laid flat upon a large gridiron, raised about two foot above a charcoal fire, with which it is surrounded.” It wasn’t until the latter part of the 20th century that “barbecue” in English came to refer to the apparatus used for this manner of cooking.

Now, it bears mentioning that there are some very insistent francophones online who attest that barbecue comes from an expression, “de la barbe à la queue”, or “from beard to tail,” an expression from French-Canadian trappers, referring to spit-roasting whole animals. I haven’t found any solid evidence to that effect, but if anyone out there can find some evidence more compelling than a sentimental thinkpiece (for instance, usage of the term dating before the 1530’s), I would be keen to know about it.

Of course, I am not so bold as to assert that the Taíno invented this method of cooking. Humans have been cooking meat over fire since time immemorial. However, thanks to the wealth of credible information that exists, I am daring to assert that it is, indeed, a word of Taíno (sometimes credited as Arawak) origin. (Who could imagine that such a tasty bit of culinary history DOESN’T involve the French? Scandalous!)

The Taíno language has given us much more vocabulary than just “barbecue.” We know that Columbus recorded the word “canoe” on October 28, 1492; it was subsequently used in English for the first time in 1555, in Richard Eden’s translation from Latin of a travelogue called The Decades of the Newe Worlde, or West India, Etc. by Peter Martyr. Hurakán (from hura, or wind) entered Spanish in the 16th century (huracán), which finally made its way into English. Words like tabaco (tobacco), hamaca (hammock, or “bed made from the bark of a hamack tree”), and mahiz (maize/corn) had a similar linguistic trajectory.

English is as a language that is open to, and has been shaped by, outside influence. From the beginning, Old English was subject to influence from the Celts, the Romans, and later the Normans. During the Renaissance, Romance and classical languages injected more vocabulary into the English language. In the 16th century, both Spain and Britain were world powers, and resulting cultural exchanges brought about changes to the English language. When the Spanish colonized large swaths of territory in the New World, the Spanish language received an influx of Indigenous words to describe objects, places, and various phenomena that they had never interacted with before. The Spaniards subsequently brought these words back to Europe, and voilà, the evolution of the English language.

American English saw further influence during the westward expansion, under the idea of Manifest Destiny (or, “We’ve decided this land is ours; we’ll just go ahead and take it off your hands.”) Again, by way of violent conflict, the language acquired more Spanish loanwords, some of which were of Indigenous origin. Despite the evolution of English due to foreign influence over the course of hundreds of years, when it came to acquiring Indigenous words directly, American settlers were less receptive. According to this quote from Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt: “We have room but for one Language here and that is the English language, for we intend to see that the crucible turns our people out as Americans of American nationality and not as dwellers in a polyglot boarding house.” Linguistic influence, we can therefore assume, was acceptable and normal when it came from Romance or classical languages, but not when it came from the Indigenous peoples they were trying to snuff out.

Despite all this, today there are thousands of loanwords that come from the Indigenous peoples of North and South America. Some came directly into the English language, and others came by way of another language, as we have seen here with Spanish.

Over the last 30 years, there has been a growing movement to revive the Taíno identity, directly defying the long-held mainstream belief that our ancestors were completely eradicated.

How does the culture persist and how is it transmitted? We need look no further than elements of language, culture, knowledge and customs that thrive to this day, embedded firmly in households throughout the Caribbean islands and the diaspora.

Recent genetic studies have proved that, in a sampling of the Puerto Rican population, there are Amerindian markers in mitochondrial DNA (which is passed on from mothers to their children). In 2003, a biologist from University of Puerto Rico, Juan C. Martínez Cruzado revealed results of an island-wide genetic study. Out of 800 subjects, 61.1% had mitochondrial DNA of Indigenous origin. In 2019, researcher Maria Nieves-Colón and her team demonstrated that there is “genetic continuity” between pre-European contact Taínos and living Puerto Ricans, as well as Amazonian peoples. This confirms the theory that Taínos originated from people who migrated from modern-day South America into the Caribbean. (Watch her interview here.)

In addition to the genetic heritage of modern Antilleans and Taíno words that we still use, there are communities where people continue to employ traditional methods of architecture, farming (using a heaped-earth technique), fishing, plant-based healing, and more. It exists in rituals, forming communities, creating visual art and music, and even recreating the language, Taíno-Borikenaík.

The numbers clearly show that this resurgence in Taíno identity is gaining traction. In the 2000 census, 13,336 Puerto Ricans chose “American Indian” as their race. 10 years later, 19,839 people did so (which represents a 49% increase). Time will tell what the 2020 census reveals, and I look forward to seeing that information when it is released.

If you try to kill a people, but their words, art, customs, and blood exist to this day, can we really say that they are gone?

There is growing scholarship to further understand not only more about the Taíno themselves, but the revival of Taíno identity. One person doing such work is Christina González, a PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, who was a consultant for the recent Smithsonian exhibit entitled “Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean.”

Affirming Indigenous identity challenges the idea of “extinction.” It means rewriting the history that colonialism etched into our minds, and rejecting terms like “Indio” in favor of “Taíno” or “Indigenous.” González writes:

“From a disappeared people to contentious minority identity, the current Smithsonian exhibition marks a turning point in Taíno ethnogenesis. It reflects a shift in mainstream understandings of the Caribbean by celebrating its Native legacies and viewing them as part of Caribbean people’s patrimony, while simultaneously recognizing modern Taíno as heirs to that legacy and taking their resurgence movement seriously within a museum that represents contemporary Indigenous realities. The grand areíto [religious song and dance] of unity at the exhibition’s opening reception signals the progress of Taíno life today: Taíno are many, Taíno are diverse, Taíno are in process; but above all, Taíno are moving forward together as a people that embody the will, ingenuity, and agency to be and become as they determine.”

In light of this, I am forced to ask myself: Why is it that my legitimacy to claim my heritage is contingent on ever-changing benchmarks?

What if I carried that space of belonging inside of myself?

What if, by virtue of my existence, I could legitimize my identity without jumping through endless hoops?

If little Me had known all this, perhaps she would have felt less shame, or like she was less of a fraud. If only she had known that she had a place to fit in, and all she had to do was take it.

If I could talk to her, I would tell her that she is a true daughter of the diaspora.

Works Referenced

- “Arawak.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Arawak Accessed 13 July 2020.

- “Barbacoa Taína.” Youtube: Eat, Drink, Share, Puerto Rico. 30 July 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Iiokkx6cGo&t=2s Accessed 14 July 2020.

- “Barbecue.” Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/barbecue_1?q=barbecue Accessed 14 July 2020.

- Carney, Ginny. “Native American Loanwords in American English.” Wicazo Sa Review, vol. 12, no. 1, 1997, pp. 189–203. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1409169. Accessed 12 July 2020.

- Davidson, Alan and Tom Jaine, ed. The Oxford Companion to Food, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- González, Christina M. “The Renaissance of a Native Caribbean People: Taíno Ethnogenesis.” Smithsonian Magazine. 3 October 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/smithsonian-latino-center/2018/10/03/renaissance-native-caribbean-people-taino-ethnogenesis/ Accessed 14 July 2020.

- González, Félix Rodríguez. “SPANISH CONTRIBUTION TO AMERICAN ENGLISH WORDSTOCK: AN OVERVIEW.” Atlantis, vol. 23, no. 2, 2001, pp. 83–90. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41055027 Accessed 12 July 2020.

- Leal Spengler, Eusebio. “El español, instrumento de integración iberoamericana y de comunicación universal.” Instituto Cervantes / Congreso Internacional de la Lengua Española.” https://congresosdelalengua.es/cartagena/ponencias/seccion_1/11/leal_eusebio.htm Accessed 12 July 2020.

- Poole, Robert M. “What Became of the Taíno?” Smithsonian Magazine. October 2011. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/what-became-of-the-taino-73824867/ Accessed 13 July 2020.

- “Remembering the Tainos,” Jamaica Information Service. 10 November 2008. https://jis.gov.jm/remembering-the-tainos/ Accessed 12 July 2020.

- Upton, Emily. “The Origin of the Word Barbecue,” Today I Found Out. 12 December 2013. http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2013/12/origin-word-barbecue/ Accessed 12 July 2020.

I have been working on Jennifer Lopez’s ancestry. As you are curious so am I in our personal histories. One of my projects yielded the connection between Mookie Betts and Meghan Markle ( Boston Globe). From the records I have found, I believe Jennifer is of Taino descent. I have not found any evidence on the internet that she has done her DNA. The detail of my research is compiled on ancestry.com as private however if you interested in putting a story together ( like your writing style and Taino connection) I can invite you to the site. As side notes, Jennifer’s aunt named her daughters Taina and Tiana. Also Alex Rodriquez who is from the Dominican Republic may have a Taino connection but I have not started his ancestry. You can reach me at the email below.